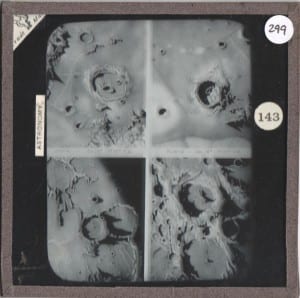

The UCL Grant Museum and the Science and Engineering Collections currently have several thousand magic lantern slides that relate to subjects as diverse as telegraphy, astronomy or Australian coral reefs; but which for the most part have been consigned to gathering dust in splintering wooden boxes. I, however, have spent the last few weeks sorting, auditing and cleaning hundreds of these slides, and I am now rather well acquainted with these little glass squares.

Example of a 19th century magic lantern slide projector from the UCL physics collection. This example was used as a sort of overhead projector but others were designed to project across a lecture theatre or hall

Magic lanterns were first developed in the 17th century as one of the earliest image projectors. While the device itself has evolved, the concept has remained the same: A combination of lenses and a light source are used to enlarge the images found on glass slides (each about the size of a Post-it) and project them onto a wall or screen. Magic lantern slides, hence, can be described as a kind of ancestor to the Kodachrome slides used in slide projectors, or even present-day PowerPoint slides.

Here are some of the highlights of what I’ve learnt from working with the collections over the past few weeks:

How the slides are made

Most of the slides are in relatively good condition, especially considering the fact that many are over 100 years old, but a few of them are quite damaged (cracked glass, faded labels and flaking tape along the edges). These slides actually provide some unexpected insight into how magic lantern slides are assembled in the first place: An image is drawn, traced or printed onto a glass plate, and in some cases a paper frame is placed around the edges. Another glass plate is then superimposed over the image and the two plates are sealed together along the edges with gummed tape (which becomes adhesive when humid).

Grant Museum magic lantern slide LDUCZ-597 showing cracked glass and damage to the photographic layer between the glass plates

For more detailed instructions, watch this 1947 video by Indiana University, which makes lantern slides seem like a fun DIY project.

DMS Watson liked to recycle

In some cases, the wooden boxes containing the slides and the labels that accompany them tell a more interesting story than the slides themselves. In the boxes containing slides made by palaeontologist and former Grant Museum curator, D.M.S Watson I found several handwritten labels, presumably by Watson himself, on the back of which are snippets of invitations to tea parties, Christmas wishes and notifications of his change of address (Photo of labels). I can only deduce from this that Watson recycled his leftover invitations by cutting them into smaller rectangles to use as labels for his lantern slide collection.

A recycled Christmas card and change of address note from D.M.S Watson re purposed here as section dividers An early admirable example of sustainable museum documentation

Another mysterious Grant Museum lantern slide from the D.M.S Watson collection showing a cas chrom, a farming tool for rocky ground LDUCZ-175

How to use Google to identify Spanish Cathedrals

Perhaps one of the most pleasant surprises amongst the Grant Museum slides was a box of black and white slides depicting an array of what I immediately recognised as Spanish cathedrals and churches. The four years I spent in the Spanish educational system have taught me to identify Gothic, Romanesque and Mudéjar architectural styles, and to distinguish between semi-circular, lancet and horseshoe arches. Thus, with a few Google searches of “fachada de catedral gótica con rosetón” (Gothic cathedral façade with rose window) or “claustro con ventantas ojivales” (cloister with lancet windows) I was able to identify the uncaptioned images of cathedrals from León, Segovia or Sevilla.

Grant Museum Lantern Slide of the cathedral at León LDUCZ-192. Why is it in the Grant Museum collection? How was it used in the past?

Another slide from the Cathedral series. Grant Museum Lantern Slide of the Cathedral at Segovia LDUCZ-196.

(However, some of these Google searches didn’t yield any results, and quite a few slides are still nameless. If anyone recognises the church in the slide below, please let me know !)

Mystery cathedral slide, LDUCZ-221, from the Grant Museum. Ideas on the identification on a postcard or better yet in the comments below.

This is an ongoing project – with several thousand more slides to unpack – so stay tuned for more!

Margaux Bricteux is a UCL Arts and Sciences student on a summer internship at the Grant Museum.